The Last Extraction

The Conference Room

The room was small, deliberately so. Twenty-three chairs arranged in a loose semicircle. No tables. Nothing to hide behind. The investor stood at the front, not behind a podium but beside it, hands in pockets. Relaxed. The way someone looks when they’re about to say something true.

These were the prodigies. Handpicked from top MBA programs, some straight from undergrad at places that mattered. Metrics, pedigree, hunger. They were here to learn how wealth actually worked, not the sanitized version from textbooks.

The investor smiled, not warmly but with recognition, like seeing younger versions of themselves.

“Let me tell you how every significant fortune in modern history was made,” they said. “It’s simpler than you think.”

The Pattern

“In 1850, someone realized you could pull black rock from the ground and burn it for energy. Coal. It powered everything. Factories, trains, entire economies. The people who controlled coal mining became unimaginably wealthy.”

A few heads nodded. This was history they knew.

“But here’s what’s interesting. Coal took 300 million years to form. The Carboniferous period. Dead plants, compressed under impossible pressure, transformed into dense energy. Three hundred million years of accumulated solar power, locked in the ground.”

The investor paused, let that number sit.

“The coal barons didn’t pay for those 300 million years. They paid for picks, shovels, and labor. The formation cost had already been paid. By time. By geology. By a process so slow it’s almost meaningless to human minds.”

One of the prodigies raised a hand. “Isn’t that just how natural resources work?”

“Exactly,” the investor said. “That’s exactly the point. Let me show you the pattern.”

The Escalation

“After coal came oil. Same structure. Millions of years of ancient organisms, crushed and cooked under the earth’s crust. Transformed into dense liquid energy. The oil companies paid for drilling rigs and refineries. They didn’t pay for the millions of years of formation. The Rockefellers, the Saudi royal family, every petroleum fortune. They monetized the gap between formation time and extraction time.”

The investor clicked through slides. Not slick graphics but simple timelines. Formation time in millions of years. Extraction time in decades. The delta between them labeled simply: profit.

“Minerals. Rare earths. Lithium. Gold formed in the hearts of dying stars, scattered across the early earth, concentrated through billions of years of geological sorting. Mining companies pay for the dig. They don’t pay for the supernova.”

“Timber. A redwood forest takes 500 years to reach maturity. You can clear-cut it in a week. Someone owns the land, pays the loggers, sells the lumber. The 500 years of growth? Free.”

“Fish. Factory trawlers in the 1960s found ocean populations that had built up over centuries of natural reproduction. They harvested in seasons what had taken generations to accumulate. The fishing companies paid for boats and nets. They didn’t pay for the centuries of fish breeding fish.”

The room was quiet now. The prodigies were doing the math in their heads. Formation time versus extraction time. The gap was where fortunes lived.

“Every boom,” the investor said, “happens when someone finds a substrate that took a long time to form and figures out how to extract it quickly. The wealth isn’t created. It’s converted. You’re turning stored time into immediate value.”

The New Frontier

“So here’s the question,” the investor said. “What’s left?”

A pause. Someone in the back shifted in their seat.

“We’ve extracted most of the easy geological stuff. The coal seams are mapped. The oil fields are drilled. The old-growth forests are gone. The fish stocks are depleted or managed. The easy conversions are done.”

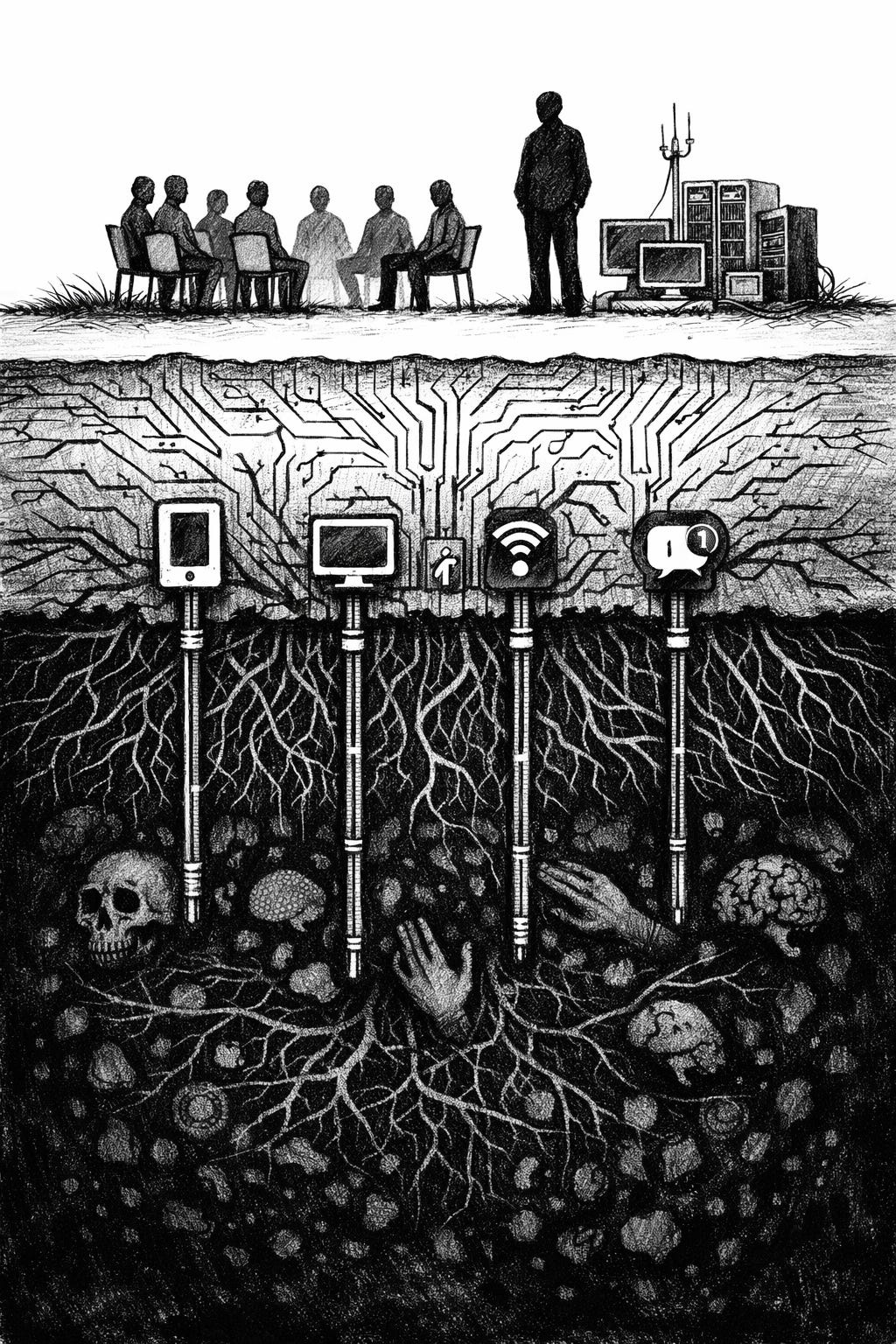

“But in the 1990s, something new appeared. The internet. And with it, a completely different substrate. One that hadn’t taken millions of years to form like oil or coal.”

The investor advanced the slide. The timeline stretched back 200,000 years. Homo sapiens. The emergence of modern human psychology.

“Human attention evolved in environments where threats were immediate and social bonds were survival necessities. Your brain’s reward systems were shaped over millennia of evolutionary pressure. The dopamine hits that kept your ancestors alive. The fear responses that kept them vigilant. The social validation that kept the tribe cohesive.”

“All of that. 200,000 years of formation time. And in the late 1990s, we figured out how to extract it.”

The Room Shifts

No one was looking at their phones anymore. The air felt different.

“Facebook didn’t build the human need for social validation. That took millennia. They just figured out how to harvest it. Every like, every notification, every carefully tuned variable in the feed. They’re extraction mechanisms.”

“YouTube didn’t create the way your brain responds to novelty and completion. Evolution did that. They just built the interface to exploit it. Auto play. Recommended videos. They are just the drills.”

“TikTok didn’t invent the patterns that make content addictive. Those patterns were formed over hundreds of thousands of years of human development. Short-form video, infinite scroll, perfectly timed dopamine hits. They’re mining your paleolithic instincts.”

The investor’s voice stayed level, factual, like reading from a ledger.

“The formation cost? Paid by evolution. The extraction cost? Server farms and software engineers. The delta? We call it a trillion-dollar valuation.”

A voice from the left side of the room pushed back. “But YouTube does provide value. I’ve learned so much from it. Educational content, tutorials, entertainment I actually want. That’s not just extraction.”

“Of course it provides value,” the investor said. “That’s how extraction works at this scale. You need the user to feel like they’re winning.”

A slight smile. “If you feel genuine gratitude toward the platform, they’ve done their job perfectly. The value you receive is real. It’s also the cost of customer acquisition. The free sample that gets you onto the extraction platform. The question isn’t whether you get something. The question is: what’s the ratio between what you give and what you get? And who sets that ratio?”

Another spoke up, voice uncertain. “But that’s different. We’re not depleting anything physical.”

“Aren’t we?” the investor said. “Attention is finite. The capacity for genuine connection is finite. The ability to focus deeply is finite. We’re not extracting rocks from the ground. We’re extracting cognitive capacity from people. And unlike oil, which you can stop pumping, this extraction is continuous. Every human, every day, having their attention harvested.”

“The coal ran out eventually. The old-growth forests are mostly gone. The fish populations crashed. What happens when you deplete human psychology? When the substrate itself changes because you’ve extracted from it too aggressively?”

The Silence

The investor looked around the room. These were smart people. They could see the shape of it now.

“Topsoil used to take 500 years to form an inch. We’ve depleted it in 150 years of industrial agriculture. Attention spans used to hold for sustained periods. We’re seeing them collapse in a single generation of smartphone exposure.”

“The coal barons didn’t think about what came after coal. The factory trawler captains didn’t worry about what came after the fish were gone. They optimized for extraction during their lifetime. And the tech founders, the platform builders, the algorithm designers, they’re doing exactly the same thing.”

“Every major fortune followed this pattern. Find something that took a long time to form. Extract it quickly. Monetize the gap. That’s not a moral judgment. It’s an economic one.”

Someone in the front row asked the question everyone was thinking. “So what comes next? After we’ve depleted human attention, what’s the next substrate?”

The investor let that land.

“There’s plenty left if you look hard enough. Emotional regulation. The capacity for deep relationships. Consciousness itself, if we can figure out how to quantify it. Human substrate is remarkably deep. And unlike coal seams, it regenerates. Slowly.” The investor paused. “Well, if it regenerates fast enough, we’ll have another shot at it.”

Someone who hadn’t been nodding raised a hand. “But what about real innovation? The transistor. The semiconductor. Those created genuine value, didn’t they? Not just extraction.”

The investor nodded. “A brilliant example. Thank you.”

They advanced the slide. Instead of a comparison, it showed a timeline from the transistor to the present.

“The transistor was creation. A singularity. But what happened next? We spent decades miniaturizing it. Making it faster, cheaper, smaller. Why? To build the perfect vessel. The smartphone. The server. The device that could finally, efficiently, connect to the real substrate: the human nervous system.”

They leaned forward. “The semiconductor was the steam engine. A magnificent invention. But its ultimate economic purpose wasn’t to be admired. It was to power the pumps that drained the coal seams faster than ever before. You’re asking about the engine. I’m teaching you about the mine.”

A pause.

“Look at the timeline after that invention. The transistor was invented in 1947. The semiconductor fortunes didn’t really arrive until the 1980s. Thirty years of patient building. Incremental improvements. Compounding returns. Decades of waiting.”

The investor pulled up another slide. A simple comparison.

“Facebook was founded in 2004. By 2009, it had a ten billion dollar valuation. Five years. Why? Because the Facebook founder didn’t have to build human social instincts. Those took 200,000 years to form. He just had to extract them. He built an interface to harvest what already existed.”

“We don’t want to wait 30 years anymore. The market doesn’t reward that kind of patience. LPs want returns in 5 to 7 years, maybe 10 if you’re lucky. You can’t compound value that slowly and stay competitive. So we find substrates that already formed, and we extract quickly. That’s where the velocity is.”

A confident voice spoke up from the middle of the room, more calculated than the others. “What about habits? Human habits form faster than evolutionary instincts. Even decade-old routines, daily patterns. Most behavior is unconscious, reactive. Could we extract from those?”

The investor considered this. “Good question. Habits are interesting. They form on human timescales but still represent accumulated time. And yes, they can be leveraged without conscious awareness. That’s worth exploring. Bring me three concrete examples next week.”

A different voice, quieter. “So why not build something instead? Why not create new value rather than extract what’s already there?”

The room shifted. A few people glanced at each other. The question felt naive, but it was the question.

The investor didn’t dismiss it. They nodded, like they’d been waiting for someone to ask.

“Because destruction is always easier than construction,” they said simply. “Construction takes time. Real time. You can’t shortcut it. An old-growth forest needs 500 years. A fish population needs generations. Trust in an institution needs decades of consistent behavior. Human attention patterns needed 200,000 years of evolution.”

“You can build things, absolutely. But building creates value slowly. The returns compound over time. That’s not where the big money is. The big money is in the gap. Find what took ages to form, extract it quickly, capture the delta. That’s the pattern. That’s always been the pattern.”

The questioner looked down.

“And that,” the investor said, looking around the room, “is what I’m paying you to figure out. What’s left that took a long time to form? What can we extract before someone else does?”

What Remains

The prodigies filed out slowly. Some were texting already, thumbs moving across screens in practiced patterns. Others walked in silence, thinking.

One of them paused at the elevator, a thought half-forming. Something took 200,000 years to build, and we extracted it in five. But what if you didn’t need to wait for nature? What if you manufactured the dependency in days and provided the relief in minutes? Create the craving, sell the satisfaction. Scale that across millions of people. The formation time collapses to nothing. The extraction becomes continuous.

The thought didn’t finish. The elevator arrived. They stepped in, and the doors closed on a room that was already empty.

Have not read such a very thoughtful and deep observation on exploiting natural resources formed over millions of years - paying only for their extraction ( technology and labour) and not for formation. Nature and time are treated as 'free"! But then, without reward, no one would invest in exploration and extraction. Of course the same pattern seen in the case of internet also. For extraction of natural resources companies should pay to society and in the case of data, people must be compensated for their attention/time and their data. Society can gain more by restoration and sustainability.

I really liked this article, placing human attention in the realm of natural resources extracted by "Investors" is a novel idea I had never heard of before.

The idea of attention as a mineable resource hits really well given the context provided in this article. First presenting the limited resources of Coal, Trees, Fish, and Oil really helps paint a tangible feeling to help put the idea that "Attention is finite".

Not using the word capitalism in the article a single time and instead using "Investor", "MBA Prodigies" really helps paint the picture, I believe Capitalism is a very loaded word and appreciate the word choice.

I think that this as a stand alone piece works great, but it's got me thinking. It speaks to one emotionally which is very important. There is more to be done in digesting the meme, "Attention as a mineable resource". For example, What really is attention, why it is valuable, what are products it defines, what is the history of attention as a mineable resource. These questions would be a good starting off point for future discussion. For example we think of Facebook and Tik tok as attention mining systems, but before the internet we also has TV(Idiot Box), Magazine, Taboilds, and News Papers as systems of mining attention. There's a fun "The Medium is the Message" allegory to be made here I don't quite have the media literacy to articulate.